Joan Margarit: “Fer un poema és molt més difícil que morir-se”

Accés a l’entrevista al diari Ara:

https://www.ara.cat/suplements/diumenge/poema-mes-dificil-que-morir-se

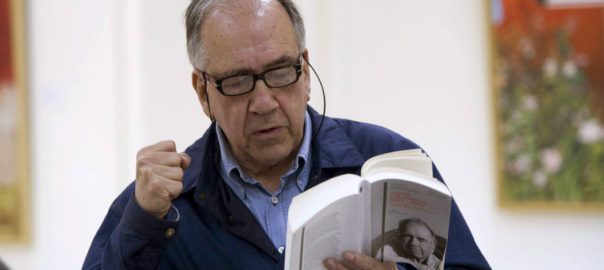

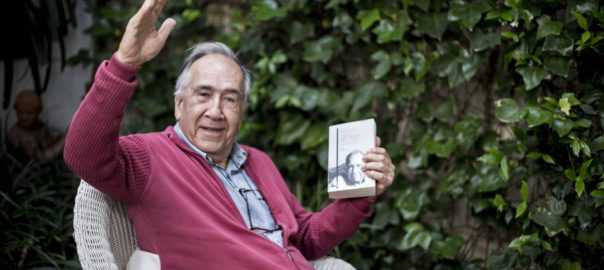

Joan Margarit em convida a fer l’entrevista amb l’excusa de la publicació del seu últim llibre ( Per tenir casa cal guanyar la guerra, editada a Proa) a casa seva, a Sant Just Desvern. Com que hi arribo uns minuts abans de l’hora intento endevinar quina de les casetes és la de l’arquitecte. L’exercici no és difícil si has llegit el poeta. És una casa sòlida, de poble, de les de pati al darrere, sense pretensions ni mandangues. Confortable i lluminosa, impecable i càlida. Quan passo per davant per mirar-la, Margarit obre la porta i em crida amb amabilitat. M’ha vist per la finestra de la cuina i em convida a fer un cafè amb caramels de cafè amb llet. L’entrevista no comença ni acaba formalment, Margarit parla pels descosits i tot s’aprofita. Quan arriba en Francesc Melcion per fer les fotografies, li agraeix els seus poemes, i mentre treballa anem parlant de com ens ha ajudat a tants lectors quan la pèrdua et llança a la intempèrie. Hi ha una fotografia de la seva filla Joana i pregunto si va escriure sobre la seva mort en calent.

“Aquesta vegada m’ho salto i no faig els poemes en calent, els faig en roent. I si no surten, a fer punyetes la poesia. Vol dir que en el moment clau m’ha fallat. Aquest va ser el plantejament. Tothom està d’acord que res en calent. Però si tens una eina com la poesia, l’has de poder fer servir sempre… Et diria d’anar al despatx, però no n’he tingut mai”.

I on escrius?

¿On vols que escrigui, si només necessito un paper i una ploma?

Molts anys als bars, no?

A tot arreu. No he tingut mai despatx a casa i ara en tinc, perquè som sols en aquesta casa i em van dir que en tenia un.

En Francesc i jo mateixa creiem que ets un poeta que ajudes el teu lector.

Això ha de fer un poeta. O què ha de fer? Destorbar-lo? Deixar-lo indiferent? Per a què serveix, l’art? En aquestes memòries, que en diuen, hi ha una recerca d’un problema molt senzill. Per què he escrit aquests poemes? Em trobo als 80 anys que dec haver escrit uns 1.000 poemes a la meva vida, i en dec haver publicat uns 750. Per què he fet aquests poemes, i no uns altres? Per què no he escrit uns poemes com els d’Espriu, o com els de Foix, Celan o Yeates? He escrit aquests, per què? En el fons, perquè soc jo i no un altre. Aquesta pregunta també vaig pensar que era molt paral·lela a qualsevol lector. La cerca d’un mateix és universal. Aquest episodi que no em podia plantejar fins que hagués escrit els poemes havia de ser una recerca de solitud, i també podia servir de pauta o mirall.

Una experiència personal que és universal.

El que busquem en l’art, tant en un quadre de Gauguin com en una sonata de Haydn, o un poema, és dir “I si soc jo?” Aquest “I si soc jo” és el màxim consol. El nostre consol és mirar-nos al mirall. No en el sentit xulesc, sinó en el de penetració de veure’t en un lloc on pensaves que no sortiries. Et pots veure en un mirall que et dona una visió més profunda teva. Aquest és l’objectiu. Comprensió. Quan moltes vegades et diuen que una poema ha fet plorar, és perquè el lector ja estava en les condicions necessàries per fer-ho, i en afegir-hi el poema s’hi ha quedat. Aquest quedar-t’hi és el que busques, és el consol. És el refugi contra la intempèrie. Com que tot això fonamental t’ho has de fer tu i no t’ho fa ningú per tu, el poema et dona eines perquè tu vagis fent aquesta casa. Per tenir casa, cal guanyar la guerra. Quina guerra? La teva, evidentment.

La casa com una extensió d’un mateix.

La casa va ser també l’atzar, que influeix molt. La vida va molt ràpid; tots els tòpics com “Es pot aprendre dels errors” són romanços. Quan acabes de fer un error ja estàs preparant el següent. I si t’entretens gaire aprenent d’aquest error, el següent encara serà pitjor. Va tan ràpid que no tens temps de res. Per tant, l’atzar ha de ser favorable perquè descobreixis coses. Vaig tenir un moment, que s’explica al final del llibre, en què vaig poder enfilar el camí. En faig un resum. Acabo de fer l’ingrés a arquitectura. I cal veure què significaven les carreres d’enginyeria aquells anys, des d’abans de la guerra i la República, fins i tot, fins als anys 60 avançats, que per fi van canviar els plans d’estudi. Les enginyeries eren les que els poders, i especialment durant el franquisme, van destinar a ser les carreres del futur. El poder va decidir que els fills dels rics serien enginyers. Així no hi hauria problemes. Com s’assoleix això? Molt fàcil. Enginyeries, totes a Madrid. Alguna a Barcelona, industrials i tèxtils. Agrònoms, camins, comunicacions, a Madrid només. I l’arquitectura es considerava una enginyeria i es feia a Madrid i Barcelona. I prou. Enlloc més. En segon lloc, hi havia un ingrés brutal. Brutal vol dir que si anaves a fer els exàmens de dibuix, de 300 alumnes n’aprovaven sis. Punt. El meu curs en vam ingressar 15. Això deixava els pobres fora de joc. Era una carrera de rics, tant que fins i tot n’hi havia com els enginyers de camins que sortien amb feina a l’Estat des de la facultat.

Dius que vas tenir un cop de sort.

Vaig ingressar-hi en tres anys. Tot eren felicitacions, en aquell moment. Jo estava venint amb el vaixell des de Tenerife, i ja volia ser poeta. I què fotia aquí d’arquitecte, si volia ser poeta? I deixo la carrera. Me’n vaig a treballar a una editorial. Per sort, a l’editorial em posen a fer un diccionari tecnològic que consisteix a copiar-ne tres de ja existents. Quan fa dos mesos que copio, em dic que potser no era això. Si el lloc per ser poeta era això, potser l’estàvem espifiant. Llavors es produeix un altre element atzarós: no en puc dir afortunat ni de sort.

Les inundacions del Vallès.

Amb 20 morts. Les veig de molt a prop. El meu pare, que era arquitecte del Ministerio de la Vivienda, el fan de seguida del comitè d’emergència, ajuda i reconstrucció del drama aquest. Aquella mateixa nit, jo la passo portant el meu pare en cotxe a l’Hotel Regina, on hi ha el quarter general de vigilància. Passo la nit a la vorera del davant, amb tota la tromba d’aigua, dins del cotxe, escoltant la ràdio. El meu oncle era a Rubí traient gent de l’aigua, i després m’explicaria com molts li relliscaven i l’aigua se’ls emportava. I m’adono del que és una casa. Es va endur totes les cases fetes a la llera del riu. Em ve a la memòria una de les coses que ens havien explicat, o havia llegit, a l’ingrés d’alguna assignatura: el codi d’Hammurabi. El primer codi civil de la humanitat. Quin és aquest moment en què la humanitat fa el gir, i té fins i tot codis civils? El moment en què deixen d’anar a les coves i fan cases. És el gran moment estel·lar de la humanitat, quan decideix que no cal buscar forats per anar a dormir, es pot fer una casa al costat del riu, si vol. Ja veurà els perills, després. Però pot fer-se cases. I és quan ve el codi d’Hammurabi. Ve perquè fa ja 100 segles o no sé quants que es va passant de la cova a la casa. I diu el que després diran: si la casa cau i mata el fill de l’amo, matarem el fill de l’arquitecte; si mata la dona de l’amo, matarem la dona de l’arquitecte, i si mata l’amo, matarem l’arquitecte. Això ja no és així, però sempre he viscut amb l’avís dels advocats present: si cau una casa, no t’entreguis mai el primer dia; ves-te’n i entrega’t al cap de 15 dies. Els arquitectes hem viscut amb això, i et puc explicar nits sinistres sobre aquest tema. Una casa ha de ser segura, ha de ser el teu lloc. Com es fa una casa segura? Quina seguretat té una casa? Com saps quina té casa teva?

No ho sé. Hi confio i prou.

Casa teva, suposant que estigui ben feta, té una seguretat d’1/30.000. Això vol dir que si fem 30.000 cases com la teva, en caurà una. Però no saps si és la primera o l’última. Sempre hi ha un punt de desconeixement. I el país ric té una seguretat d’1/50.000 o 1/40.000. El país pobre no en té cap. O la té més baixa. Per això quan es produeix el terratrèmol dels anys 50, moren mig milió de marroquins. I el mateix terratrèmol al Japó, als hotels continuen prenent el te. Perquè un ha construït una casa d’1/30.000-40.000, i l’altre és d’1/3.

En aquell moment cristal·litzen la poesia i el càlcul d’estructures.

Noto que això és a prop de la poesia. I que fer diccionaris per a una editorial o entrar a la carrera d’arquitectura a fer de decorador, a la poesia no li agrada. Però lligo caps i noto que a la poesia, la seguretat de la casa i la persona, la intempèrie, buscar refugi, sí. I he de tornar a l’escola per buscar aquesta zona. Llavors començo les assignatures de càlcul i comença la meva vida de poeta i arquitecte.

L’arquitectura i la poesia estan tan juntes que escrius poesia quan allargues les visites d’obres.

Més de la meitat de les meves obres estan escrites en bars de paletes, per entendre’ns. El primer que feia quan anava a una direcció d’obra era mirar on eren els bars del voltant. Això, naturalment, l’hi preguntava a l’encarregat i als paletes, que de seguida ho sabien. Un dels poemes que m’estimo més és un que es diu Recordant el Besòs. És per un projecte d’arquitectura. Més que d’haver fet l’Estadi de Montjuïc, hi ha tota una part meva que m’estimo moltíssim, potser la que més. És una llarga temporada durant la qual el nostre estudi va estar reforçant, mantenint i posant al dia tots els habitatges que es van fer durant el franquisme als anys 40 i 50, amb les primeres migracions espanyoles; primer la dels murcians i després la dels andalusos, bàsicament. Havies d’entrar a la casa d’aquesta gent, pobra, que portava 40 anys vivint en uns règims a qui se’ls en fotien els pobres. No es refiaven de tu, perquè anaves amb americana.

A primera vista, formaves part dels altres.

I anaves a fer unes coses que sabies fonamentals. Eren edificis sense fonaments. Edificis que no lligaven amb la claveguera i portaven 30 o 40 anys tirant la porqueria al seu soterrani, on no baixava ningú perquè era tancat hermèticament. Però què hi passava? Si hi tires la porqueria, els gasos estan a punt d’explotar. Havies de saber que per picar i foradar això, havies de demanar al paleta que apagués la cigarreta. Si el paleta la portava en fer el forat, podia saltar tot pels aires. Coses d’aquestes. Aquell poema és l’entrada en una casa del polígon del Besòs, on fèiem fonaments nous. Primer has d’entrar a totes les cases, veure i interpretar les esquerdes, veure què li passa a l’edifici i prendre decisions basant-se en aquesta interpretació. Les inspeccions eren impressionants. Els avisaves que a les 9 del matí començaven, i potser entraves a 30 habitatges. Hi veus de tot. En aquest poema, entrem en un habitatge on amb prou feines hi havia mobles. Les habitacions eren matalassos a terra on hi havia criatures i gossos. Els grans no hi eren. De sobte, a la cuina, apareix un noi de 16 o 17 anys escoltant música. Un munt de vinils mig trencats. La pica plena de plats bruts amuntegats amb verdet. No ho oblidaré mai. I el tio estava escoltant Bach.

D’aquí surt un dels teus versos més coneguts: “Per aquest món cap més futur que Bach”?

Sí. T’explico això perquè és un error dir que vida i poesia són el mateix. Aquest és el gran error romàntic. Hi ha una conferència de Stefan Zweig, ja grandet (ja no era romàntic, havia sortit Hitler i tot) en què diu que llavors començava la poesia perquè teníem un poeta pel qual vida i poesia eren el mateix… Hem cregut cada ximpleria pel fet d’embolicar-la una mica amb música o poesia! Que no sap que la vida està per sota de tot? Que la vida surt en tot? La poesia, la lampisteria, tot. Tot surt de la vida. Sigui poeta o lampista. Quina falta de sentit comú… La conya dels sentiments, que si estan al cor, i la intel·ligència, al cervell. D’aquí en avall (s’assenyala el cap) només hi ha trastos al servei d’això. Tot és aquí. ¿Això meu és amor? Si vostè estima sense intel·ligència, déu nos en guard. Què més li pots demanar a un amor, que sigui assenyat i amb intel·ligència? Si no, és una bestiesa.

Que no has fet ni poesia ornamental ni arquitectura decorativa, vaja…

Això és la poesia i per això algú diu que va ser útil. Si creiem totes les altres ximpleries, no arribem a ser ningú. Per a això serveix la poesia, un poeta, un pintor. Quan veig un quadre, el primer que em dic és si em faria plorar en una circumstància adequada. No vaig plorant per les exposicions, però si m’hagués passat no sé què, podria arribar a plorar mirant aquest quadre? Si arribo a la conclusió que no, per a mi és un quadre intranscendent. Em val per a Haydn o per a Gauguin.

També ets un poeta de la vida i de la mort, per dir-ho d’alguna manera, de la vida al complet.

Sí. L’aventura de la Joana va ser molt important, també. I també l’atzar. Era una persona amb un retard mental important, tan important que mai va poder llegir quotidianament. Podia llegir unes frases, amb molta dificultat. I l’escriptura igual. Era una persona que no podies deixar sola a casa mai, però en canvi venia a tots els concerts on anàvem. Estàvem en un concert i podia gaudir sense impacientar-se d’una simfonia de Beethoven i d’una sonata de Schubert. I era tot amor, tot afecte. Per una raó: va descobrir de seguida que l’afecte era la seva arma; no en tenia cap més. Per això quan estava dubtant amb alguna persona, li deia “T’estimo”. Era la seva eina de defensa. Quan va néixer no sabíem de què anava aquest tema, i la primera reacció és dir que no pot ser, per què t’ha tocat això, traieu-m’ho de sobre. Fins al dia que t’adones que això és la teva filla, i comences a veure les virtuts d’aquella persona. No he trobat mai ningú amb tanta bondat com la Joana. No reconec ningú. Han passat 18 anys i encara, depèn de com estic a casa, passo els dies perfecte, però sempre n’hi ha un, no saps quan, que t’atures davant un retrat i et fots a plorar. 18 anys després. I content de fer-ho, a més. És una manera. Tot serveix per a l’alegria. Si el panorama el tens ben traçat i les vies d’arribada als llocs les tens ben estudiades, gairebé tot serveix.

El problema és el trànsit, no?

Esclar. El problema és saber els camins. I hi ha gent que no en té ni idea. La cultura, que en diem, no són castellers, futbol o política. La cultura és això, el que et permet fer una via entremig de tot aquest desgavell, entendre’t i arribar a llocs on de sobte no fa fred. La cultura que no serveixi per a això, ja te la regalo. L’illa del tresor de Stevenson serveix per a això. Una mala novel·la no serveix per a res.

El trànsit només es pot fer amb la cultura?

Amb la bona cultura. Dins la massa de la cultura es cola tot, i tu has de fer la tria.

I l’amor?

L’amor és molt complicat. Es barreja amb la supervivència. En un dels últims poemes que he escrit, hi ha un vers que, no sé per què, m’estimo molt i diu “L’amor no són els fills”. És una altra cosa. Dedicació, vigilància, el que vulguis, però no sé si és amor. Diria que no, que és una altra cosa que fem encantats, que ens porta alegria, però no sé si és aquesta paraula. L’amor és més a prop del desig. El desig és bàsicament ignorància. Per desitjar una cosa has d’ignorar-la. Quan saps perfectament què és aquella cosa, no la desitges. T’hi pots entendre, però no la desitges. Per això la famosa tristesa post coitum. És que abans ignores i ho desitges, i quan acabes de fer-ho se’n va el desig. Llavors entens què és allò, i s’ha acabat la història. Arriba la tristor de no haver-te’n adonat.

Una vegada em va dir un senyor molt gran que l’amor és un malentès.

És ignorància. Evidentment. Perquè tu miris la lluna i et recordi aquella senyora amb qui vols anar-te’n al llit i estimar-la. Home, per fer aquesta jugada has d’oblidar-te de què és la lluna. Un tros de pedra flotant a l’espai. Te n’has d’oblidar i l’has de fer símbol d’una cosa que torna a ser una altra trola. És una altra cosa, també. I tot això va passant a la velocitat que va la vida, com una autopista sense sortides laterals ni gasolineres.

Potser és també una qüestió de voluntat, aquesta ignorància o malentès. Hi has d’estar disposat.

Crec que és el problema de la col·lectivitat. Som una espècie que s’assembla més a les abelles i formigues. Si no viuen en comunitat, es moren. Tu no tens defenses sol. Per tant, has de viure en comunitat. La mateixa comunitat s’arma de solucions perquè allò sigui possible. La comunitat et menteix sobre coses com aquestes. T’ha de mentir, el tram tan ràpid de la vida té dos extrems nítids. No dic nets perquè sembla moral, i parlo de característiques. El primer és nítid perquè no té cap brutícia prèvia i ho ha de fer tot en quinze anys. Són els fonaments de la casa, que és el que busca aquest últim llibre. Són els fonaments de la persona. No és la casa, no saps si tindrà ornaments, ni quantes finestres hi haurà, ni quina façana tindrà. Però no tot és ignorància; si veig fonaments, sé que en aquells fonaments es pot fer una casa de sis pisos, però no de 30. Sé si tindrà dues façanes o quatre. Sé moltes coses, però no ho sé tot. Vindrà la vida, amb tots els seus atzars, i farà la casa. Però el fonament diu moltes coses, si el saps mirar. Tantes, que pràcticament t’explica els poemes que faràs quan tinguis 50 anys. L’altra edat així de nítida és la senectut, l’altra punta. Però té una característica: qualsevol edat serà jutjada per tu mateix des de la següent. Quan ets una persona madura, jutges la joventut que has tingut. Això passa amb totes les edats menys amb una, l’última no la jutjaràs. Ni tu.

Què et dona, això? Llibertat?

Exactament. Et pots morir d’un càncer, però seràs lliure. No suportaràs cap judici. Això és importantíssim. Són les dues úniques edats. La primera no la jutjaràs perquè no pots jutjar una infància. I la senectut, pel mateix motiu tampoc. Tot això del mig és el que en dic el lío. Perquè la paraula catalana no em serveix. Embolic és una gilipollada comparat amb el lío. Embolic mai pot ser un drama, i un lío pot ser dramàtic. Aquest lío és necessari, a més. Si el desfessis, no hi hauria ni pa als forns ni carn als supermercats, ni arribarien els trens. Hi ha de ser, però és un lío. Quan em diuen si continuaré les memòries, no em vull ficar més en el lío. Ja n’he sortit.

El ‘lio’ està explicat als poemes?

Si en alguna lloc és, és als poemes. Tu pots fer unes memòries del lío si ets el Churchill. En el fons no fas una introspecció teva. Has estat en un lloc on has vist més coses que la resta de mortals, i si tu fas unes memòries d’aquesta zona del teu lío, explicaràs coses de la Segona Guerra Mundial. Hi ha casos en què són importants. Però per a una persona que hagi tingut una vida senzilla sense grans coses, què has d’explicar? No té cap interès. La veritat ha de ser saber sempre el que busques. Pots fer una obra d’art o una mamarratxada. Però has de saber què busques.

Sempre saps què busques, quan escrius un poema?

Sí. Moltes vegades el poema et vol dir el que està buscant i no t’ho diu bé, i d’entrada no ho saps. Però si continues treballant el poema, quan pots dir que hi ha un poema, és quan al cap d’un temps sap el que busca. A vegades són pures intuïcions després de temps treballant sense saber cap on va.

Et sorprèn a tu mateix?

Hi ha sempre un moment d’incertesa en què una intuïció, la inspiració, pot ser falsa. O que tu siguis tan patata que no sàpigues interpretar-la i no te’n surtis. Perquè serveixi, cal saber què vol dir i què estàs buscant amb aquella inspiració, buscar-ho i trobar-ho. I muntar-ho amb unes paraules que li puguis enviar a una persona. Si no pots enviar-ho, no serveix per a res. Jo no em llegeixo a mi mateix. Ben mirat, la ximpleria és el poeta que escriu per a ell mateix. Escriu un diari íntim, i tampoc el llegiràs perquè és el més avorrit que hi ha.

Per a qui escrius?

Per a tots els altres. És l’única manera que he trobat en la meva punyetera vida de complir. Estimar els altres. No em puc posar a estimar una persona que acabo de conèixer. Com es fa, això? La meva dona i els meus fills sé com estimar-los, però sortint d’aquest cercle no en tinc ni idea. Cada un ha de buscar la seva manera. La meva eina és aquesta.

Aquestes memòries parlen dels fonaments de la teva infantesa i joventut. Com els definiries?

Un nen, si no li pegues i l’alimentes, no sap si és infeliç. Com després de la guerra, que hi havia nens feliços. A mi no em van pegar i m’alimentaven. Els deu primers anys de la meva vida devia viure en quinze domicilis. Sense escola i canviant de casa vol dir sense amics, vol dir soledat. Però li dius a un nen que no sap que no s’ha d’estar sol i s’espavila. Records d’infància malaurada no n’hi ha ni un. El tió a Sanaüja només portava una cosa, dues taronges. I recordo l’espectacle de veure-les baixar.

Però descobreixes què és la bellesa.

Recordo la Devesa de Girona. Immensa, fora de la ciutat llavors, absolutament sol, i recordo la tardor. Saps el que és aquella Devesa infinita d’arbres, els plàtans alts, i que de tots comencen a caure fulles. O sortint a la terrassa de casa i veient aquesta foto de teulats i catedral. I la meva mare, que potser portava sis mesos sense veure-la, i tenia un cert neguit per ella. Mirant això, el neguit baixava. Estava descobrint què és la bellesa. L’autèntic coneixement és reconeixement. De petit ho tens tot: bellesa, poesia, veritat. Però no saps que ho tens. Saber que surts a la finestra, veus Girona i et distreus d’una cosa que et preocupa. Vaig descobrir dues coses, amb això: que conèixer és reconèixer; i que si algú t’explica una cosa i no l’entens, és que no la sap.

En aquells fonaments hi ha la bellesa, l’amor de l’àvia.

El lloc on està més descrit és el poema Coratge. Tinc quatre anys, veig l’àvia pixant dreta a la vora del camí. No portaven calces. Per no esquitxar el vestit llarg, es posaven a la vora del camí i veies el raig groc. I sort en tens, d’aquella dona. I el poema acaba dient que no és literatura, no sabia llegir.

Què t’agradaria haver ensenyat als teus alumnes?

A reconèixer tots els temes aquests de seguretat. Una casa segura és un lloc on no fa fred, on no et veuen quan estàs amb la teva dona. En què els teus fills estan a recer.

Tornem a la lluita contra la intempèrie.

Si em poso vell pallisses, puc fer una apologia de la catàstrofe. La meva relació amb el futur ja és nul·la. Aquesta organització de la vida et porta a dos fracassos importants. Si no t’adones que quan ets jove has de matar el pare, en termes psicoanalítics, si no mates el pare, no et realitzes ni saps qui ets. Però és que a l’altra punta has de matar el fill, en els mateixos termes. Si no, et transformes en un vell idiota. El vell que es pensa que el millor és ser jove. Què pots desitjar, amb alegria, si no és que acabi tot d’una punyetera vegada? Jo moriré i no se m’acudirà pensar que hi ha una alternativa millor a això. Del màxim que em puc preocupar és de morir de la millor manera possible.

Veig que penses en la mort.

No tant com els joves, que com que els acolloneix… Tens fills, vas patint.

Com t’agradaria afrontar-la?

L’has d’esperar i ja està. No és cap cerimònia important. El segon on passes a l’altra banda el passem tots. Els tontos i els llestos, no deu ser gaire difícil. Fer un poema és molt més difícil que morir-se. No el pot fer tothom, un poema. Morir-se està a l’abast de tothom.

A la teva arquitectura i als teus poemes els molesta la decoració.

Em fa nosa i m’impedeix arribar on tinc ganes d’arribar en aquell moment. Per dir-ho d’una manera més pomposa, la poesia és la recerca de la veritat. No de la filosòfica, una de menys pretensiosa però més dura i profunda. No entenc que per a això s’hagi de fer un poema que no s’entengui. Si no s’entén el poema, se’n pot anar a fer punyetes.

Parlàvem de l’àvia. La mare, en canvi…

És lluny. És d’una fortalesa tremenda. Jo passo molts anys creient-me que estava incapacitada per a l’amor i que era una dona freda. Utilitzava la religió per sustentar la moral, que era el que li interessava. Perquè tenia por, estava cagada de por, i la moral són quatre referències per estar segur. Saps que quan no compleixes aquell precepte moral, estàs insegur. I si el compleixes, segur. És la manera més elemental de fer front a la intempèrie. Després ella no estava capacitada per a l’expressió de l’amor. No en sabia. Venia un cop al curs, en tren. Aquell dia que era a Girona, tenia tantes ganes de ser útil que no destinava el dia a acariciar-te, fer-te petons o dir-te que maco que ets. El destinava a veure si anaves net, estaves endreçat, si estudiaves. Per a mi era un calvari, quan venia. Desitjava que vingués, però quan venia era un calvari. Obria el llibre d’estudi i es trobava un penis entrant a una vagina. Aquell diàleg el tinc gravat aquí…: “Què és això?”; “Una marca de cotxes”; “He dit que què és això?”; “Un home i una dona fent allò”; “Qui t’ho ha ensenyat?”; si li dius algú de Girona, cagada… “Un noi gran de Rubí”. Diàleg acabat. No tenia eines. Vaig trigar molt a entendre que m’estimava amb bogeria i no sabia com dir-ho. Havia de fer tantes coses amb un fill que l’essencial se li escapava.

I el pare?

L’origen humil fent una carrera de rics era l’origen de tots els desgavells. Era un home del Barri Xino. Els dos avis també deixa’ls córrer. El meu avi era el fill de la casa més rica de Castellbisbal. I el meu besavi ho perd tot a les cartes i l’avi, amb 14 anys, va a Barcelona a descarregar carros al Born. I no torna mai més a veure la seva família. La meva àvia és filla d’uns agricultors pobres de Sanaüja i als 12 anys la porten a fer de minyona a Barcelona. Va a casa els Ramón i Planes, al lloc dels senyors de Barcelona, al carrer Ample, fins que es casa. El màxim moment d’esplendor d’aquesta gent és quan van muntar un restaurant a la plaça Reial que no els va funcionar. El meu avi li diu al pare que ha d’estudiar a la universitat, que és l’única manera. La universitat llavors era el salt social. El noi pobre que entrava en una carrera i estudiava feia un salt social. El meu pare no va portar a casa mai cap company d’estudis. Li feia vergonya. Això li va portar uns merders que van arribar fins a mi. Recordo haver tingut sempre sota el llit el capot que el meu pare portava a la Guerra Civil, amb el forat per entrar al cap tapat per una peça especial. I recordo fent servir de manta aquell capot de color caqui. Aquestes coses. Però d’infelicitat, res de res. Coses materials en necessites molt poques per no crear infelicitat. Totes les altres són per comparació.

Escriuràs més versos?

Poemes sí, n’estic fent. Sempre.

Joan Margarit, Premio Nacional de Poesía 2008 por su obra ‘Casa de Misericordia’

- Joan Margarit ha sido galardonado con el Premio Nacional de Poesía

- El Ministerio de Cultura reconoce su obra ‘Casa de Misericordia’

- Este galardón literario está dotado con 20.000 euros

- Margarit se define como poeta bilingüe en castellano y catalán

Según informó hoy el Ministerio de Cultura, Jon Gerediaga Gotilla ha quedado finalista por su obra Jainkoa harrapatzeko tranpa.El galardón está dotado con 20.000 euros, se concede a la mejor obra de poesía publicada en 2007 en español o en algunas de las otras lenguas cooficiales que se hablan en España.

El jurado que ha fallado el premio estuvo presidido por el director general del Libro, Rogelio Blanco, y han formado parte de él, Luis García Montero, Clara Janés, Pere Gimferrer y Olvido García Valdés, ganadora de la pasada edición, entre otros.

Joan Margarit (Sanahuja, Lérida 1938) es, además de poeta, arquitecto y catedrático de la Escuela Superior de Arquitectura de la Universidad de Barcelona.

Poeta bilingüe desde 1963

Margarit, que se define como poeta bilingüe en castellano y catalán. Su primer poemario, en castellano, lo publicó en 1963, volvió a publicar en 1965 y después de un largo paréntesis de diez años escribió Crónica.

A partir de 1980, inicia con L’ombra de l’altre mar, su obra poética en catalán, en la que aparecen títulos como Vell malentés, El passat i la joia o, más recientemente, Calcul d’estructures, a las que se suma las antología Trist el qui mai no ha perdut per amor una casa.

Se han publicado en castellano y catalán, además de Crónica, Luz de lluvia, Edad roja, Aguafuertes, Estaciò de França, Los motivos del lobo, Joana -dedicado a su hija fallecida- y El primer frío.

La obra premiada, Casa de Misericordia (Visor, en edición bilingüe, y Proa, en catalán) se corresponde, según el propio autor explica en el libro, con uno de los poemas que contiene y que comenzó a concebir mientras visitaba una exposición sobre la Casa de Misericordia, donde podían verse fotografías y documentos ligados a la historia de esta institución.

En la mente de Margarit, casado con Mariona Ribalta y padre de cuatro hijos, quedaron tres cosas: el edificio, enorme, austero y con los niños y las niñas “siempre graves y en orden”; las solicitudes, muchas de las cuales eran de viudas de asesinados en la represión del final de la Guerra Civil, que pedían el ingreso de sus hijos por imposibilidad de mantenerlos; y los informes de los jueces y otros funcionarios del nuevo régimen sobre aquellas peticiones.

London Grip Poetry Review

David Cooke finds Joan Margarit to be a poet of authentic experience who does not rely on tricks or strain after effect.

Love is a Place brings together Anna Crowe’s versions of the three most recent collections of poetry by Joan Margarit, the greatest living Catalan poet and, many would claim, one of the most significant poets writing in Spain today. It follows two previous English-language volumes of his poetry: Tugs in Fog (Boodaxe. 2006), a generous sampling from his first twenty years’ work, and Strangely Happy (Bloodaxe. 2011), which brought together two subsequent collections. Although Catalan is Margarit’s mother tongue, he started out as a poet writing in Spanish and was educated in that language during the years of Franco’s dictatorship, when the speech and culture of Catalonia were repressed. The poet’s bilingualism and his family’s experience of Spanish history are important aspects of his poetry, as expressed here in the opening lines of ‘Pillage’:

When I was a child they wanted me to pluck out the tongue that my grandmother spoke to me in as we came home from the fields at the end of the day. Like stones, flowers, loneliness all around, keeping us company, are words.

In ‘A History’, he faces unflinchingly his country’s past and his own family’s involvement in it:

A hundred years of war, my grandmother repeated: she was a child living in a village where every night she heard people fighting in the streets. And she would tell me, as though it were a story, about the day the soldiers dragged her mother away to be shot at dawn against the cemetery wall. When I listened to her, I too was a child, and my father, a soldier in a detention centre.

Significant, also, is the fact that Margarit is not a ‘career poet’, but was active as an architect for all of his professional life, a fact that has informed poems such as ‘Visits to Building Works’ or ‘Babel’: ‘I dreamed that I had to make the calculations / for a building of a thousand floors’ It is, perhaps, the attention to detail and the scientific discipline that is required of an architect that has shaped Margarit’s humane and unpretentious approach to the art and craft of poetry. In the eloquent prologue that he wrote for Tugs in Fog, he speaks of what poetry means to him and what he has tried to achieve in writing it. They are words well worth the consideration of any aspiring poet. For Margarit, poetry is unashamedly subjective and should arise from deeply felt, authentic experience. It is not about tricks or straining after effect. Early on, he quotes from Diderot: ‘Mediocrity is characterized by a taste for the extraordinary.’ For Margarit, as for Wordsworth, ‘poetry takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility.’ In fact, he seems to feel that the poet is almost forced to memorialize his past experience, whether he wishes to or not, that ‘forgetfulness’ is ‘a badly closed door’.

It is this truth to experience, conveyed in poetry that is uncluttered, articulate and devoid of pretension, that enables it to speak across a linguistic divide, although it should be said that Margarit has been fortunate in the close working relationship he has developed over the years with his English translator. Moreover, as Crowe suggests in her own introduction to Tugs in Fog, Catalan is a more consonantal language than Spanish and has a more staccato feel to it, which tends to harmonize well with the rhythms of English. This is exemplified in the bruised stoicism of ‘It Wasn’t Far Away or Difficult’, the title poem of the first collection included here:

The time has come when life that is lost no longer hurts, when lust is a useless light and envy forgotten. It is a time of wise and necessary losses, it is not a time for arriving, but for going away. It is now that love finally coincides with intelligence.

Here the poetry is a question of grandiloquence and measured cadences, its musicality enhanced by alliteration and vocalic harmony. It’s a poetry based on the truth and simplicity that we often seem to have abandoned in our quest for novelty and far-fetched imagery. Referring again to Margarit’s prologue in Tugs in Fog, the reader will note his insistence that ‘poetry is not a question of content but of intensity.’ While one may accept that there is some truth in this statement, the content is nonetheless important in Margarit’s poetry and focuses on what is most important to us all: mortality, suffering, isolation, and the hard-won moments of love and peace that are achieved against that backdrop. It should be noted also that if Margarit’s poetry works so well in English, that may also owe much to his affinity with certain English poets, most notably, Hardy and Larkin.

At times he reminds one also of Cavafy in his evocations of old age. In ‘Strolling’ an old man remembers himself as ‘a serious child’ who ‘has been obedient all his life’ but concludes with a beautiful evocation of human transience:

The child returns and takes him by the hand. Both of them move away until they are a dot in the sky. Birds of passage.

As with Cavafy, old age brings wisdom and a sense of resignation that is nonetheless tinged with regret. In ‘I’ll Wait for You Here’ he laments that ‘ now / no women would want to dance with him. And he resigns himself to it, but he doesn’t smile’. As in the work of the great Alexandrian, there is also candour in acknowledging one’s sexuality. Here he is in ‘Old Man on the Beach’:

Ferocious summer floods the whole space. With my gaze sliding over breasts and belly, towards the pubis of this young woman, a brutal longing is dazzling me.

However, love in all its forms is central to this poet’s work: the love between a man and a woman and that between family members and, in particular, the poet’s love for his handicapped daughter, Joanna, who died prematurely. Its importance is made clear in the final lines of ‘Love is a Place’, the title poem of his most recent collection:

Love is a place. It endures beyond everything: from there we come. And it’s the place where life remains.

Sometimes the poet evokes the seeming impossibility of maintaining love, as in ‘The Sun on a Portrait’: ‘So much talking and so much arguing / while our love was slipping away from us’. In ‘Infidelity’ loss is clouded by guilt. In ‘Suffering’ he describes the anguish of parents at the inevitable loss of a child: ‘In the Accident & Emergency corridor I saw / our helplessness in your eyes.’

In Margarit’s poetry the reader will find no easy answers. In ‘The Origins of Tragedy’, God is dismissed as ‘the most brutal of myths’. Philosophy, likewise, provides no satisfactory explanations in ‘Lyric at 70’:

Let no one search in this lyric for the big bonfires of the solstices. It is philosophers who kindle them, and religions, but they provide no warmth for the cold there is in metaphysics, which is the same as in superstition.

Ultimately, all the poet has is his poetry, a difficult and challenging art which is sometimes analogous to the rock of Sisyphus, but which nonetheless gives him solace and moments of illumination:

Poetry is the first logic. It has always spoken of the same thing, and yet, what it says is always new, just as the rising of the sun or sky at night is new.

Website: http://londongrip.co.uk

Url: http://londongrip.co.uk/2017/01/london-grip-poetry-review-margarit/

POESIA I ARQUITECTURA, UN ÚNIC CAMÍ. JOAN MARGARIT AL COAC

El proper 19 de desembre a les 19.30 h, tindrà lloc al COAC la vetllada Poesia i Arquitectura, un únic camí. L’acte començarà amb una conversa entre l’arquitecta Sílvia Farriol i el també arquitecte i poeta Joan Margarit, que presenta el seu darrer llibre Per tenir casa cal guanyar la guerra.

Seguidament hi haurà un concert de jazz, amb Carles Margarit al saxo i Albert Bover al piano, acompanyat d’un recital de Joan Margarit.

L’acte està organitzat per la Cooperativa Jordi Capell i el Col·legi d’Arquitectes de Catalunya.

Recupera el vídeo amb la conversa, el recital i l’actuació musical:

http://arquitectes.cat/ca/content/poesia-i-arquitectura-un-%C3%BAnic-cam%C3%AD-joan-margarit-al-coac

Joan Margarit, premio Iberoamericano de Poesía Pablo Neruda

El jurado destaca la calidad de su poesía y la fuerza lírica de su lengua catalana.

El poeta Joan Margarit ha logrado el premio Iberoamericano de Poesía Pablo Neruda 2017, galardón que se ha consolidado como un referente entre los galardones literarios iberoamericanos, informó el ministro de Cultura de Chile, Ernesto Ottone.

El premio le fue anunciado a Margarit, quien recibirá 60.000 dólares (unos 54.000 euros) y un galardón de manos de la presidenta Michelle Bachelet en el Palacio de La Moneda, desde la casa-museo del poeta chileno, en Isla Negra (Chile).

«Hoy, el jurado del premio Iberoamericano de Poesía Pablo Neruda ha decidido de forma unánime otorgarle el galardón al poeta Joan Margarit por la calidad de su poesía y la fuerza lírica de su lengua catalana», dijo Ottone, al darle la noticia vía telefónica.

«Es el nombre del premio lo que me desconcierta. A mis 79 años es muy importante lo que ha significado en mi vida Pablo Neruda. Tanto ha significado que tuve muchos años para poder quitármelo de encima, porque un buen maestro, un gran maestro, es tan duro para llegar a él como también para quitárselo de encima», fueron las palabras del poeta español en el momento de enterarse de la concesión del galardón.

En honor al nombre del reconocimiento, el poeta español recitó un fragmento de «Meditación», poema escrito por Neruda y catalogado por el mismo Margarit como «los versos más hermosos que se han escrito nunca». «Quiero hablar con las últimas estrellas ahora/elevado en este monte humano/solo estoy con la noche compañera y un corazón gastado por los años/ Llegué de lejos a estas soledades, tengo derecho al sueño soberano/a descansar con los ojos abiertos entre los ojos de los fatigados», declamó Margarit.

El ministro Ottone expresó su alegría por poder publicar una antología del poeta español en Chile, ya que salvo dos libros no se han publicado más obras de él. «Ello permitirá al público nacional conocer a este poeta que cuenta con una vasta trayectoria y que ha estado traduciendo toda su obra al catalán, por lo que ahora integra esa lengua al premio, uno de los más importantes de Iberoamérica y que significa un reconocimiento a la poesía, que sigue presente en nuestras vidas», añadió.

Joan Margarit (Sanauja, España, 1938) se dio a conocer como poeta en castellano en 1963 y en 1965. A partir de 1980 inició su obra poética en catalán con una estética realista y llena de un gran aliento lírico. Su obra, además, abarca una extensa variedad temática con la relación entre poesía y vida como columna vertebral de su obra, según el comunicado chileno.

Tradición lírica

Muy dentro de la tradición lírica de la poesía española, su voz es más bien íntima, clásica, tierna pero también escéptica, dura y lacerante. Siendo el suyo un lenguaje sencillo tiene un gran poder metafórico, el don de la imagen, y la capacidad de darle un giro al poema y sorprender al lector cuando pasa de lo aparentemente autobiográfico a la reflexión universal.

Este reconocimiento, creado en 2004 por el Consejo Nacional de la Cultura y las Artes a propósito del centenario del natalicio del poeta, cuenta con el patrocinio de la Fundación Pablo Neruda y se entrega a un autor con una reconocida trayectoria en el mundo de la poesía iberoamericana. Ejemplo de ello, es que en 2004 el premio Pablo Neruda fue para el mexicano José Emilio Pacheco, quien obtuvo el Cervantes y el Reina Sofía en 2009.

También ocurrió con el argentino Juan Gelman, a quien se reconoció en Chile en 2005, y obtuvo después el Reina Sofía y dos años más tarde, el Cervantes. Algo similar aconteció con la cubana Fina García-Marruz, quien fue reconocida en 2013 en España, seis años después de que recibiera el galardón chileno, y con el chileno Nicanor Parra, quien el año pasado se hizo acreedor de ambos premios.

SANTIAGO DE CHILE Actualizado:

On Life and Poetry

Essay by Joan Margarit

Translated by Anna Crowe from Catalan

Dec 4, 2016

Website: Trafika Europe

Url: https://trafikaeurope.org/essays-reviews/on-poetry/?c=cc3d3f1dd0cf

IT WAS NOT FAR-OFF OR DIFFICULT. It is here now, this time which is not mine, in which I live in a bittersweet mix of proximity and distance. I feel how strange everything around me is becoming. Already I no longer recognise some values and modes of behaviour that today are commonplace. Landscapes are changing too quickly. No, this time is not mine, but it is now, in large measure thanks to poetry, that I feel some gusts of calm happiness that years ago I never knew.

It was not far-off, this age in which nobody hesitates to think of me as old, though always with some precautions that make me smile, since they are due to the absurdly bad press that this word receives, especially when it is followed by the noun, man. Nor was it difficult to come to a natural, even pleasurable understanding of some feelings from which the young make great efforts to distance or defend themselves. Solitude and sadness, for example. I think that the acceptance of these feelings is a kind of clockwork mechanism that life sets about activating in order to place death on a familiar horizon. I have understood the most dangerous replies that the proximity of death may generate and which are to be found between two extremes: despair and headlong flight, that is to say, submission to the values of youth. And thus, too, a kind of desperation. Equidistant, there is lucidity, the step before dignity. And wonder, the threshold of love, as the alternative to resentment and scorn.

These last few years, I have realised that, while the capacity for learning dwindles, there arises, as counterpoint, another capacity which will end up being the most important: that of utilising, in order to explore new intellectual and sentimental territories, everything that has been learned in life up until now. In this way one can achieve the lucidity necessary for understanding fear. But this new capacity depends on how the development of the inner life has been achieved. There is no way of avoiding a certain irreversibility of the situation. That is what determines whether this final stretch may be the most profound, but also the most banal of someone’s life.

Fear is nothing more than the lack of love, a pit we try to fill – futilely – with a huge variety of things, acting directly, with no subtleties, a never-ending task, for the pit remains as empty and dark as ever. When you don’t understand fear, all you can attempt is this un-nuanced action, which is that of selfishness, because it can take account only of filling one’s own emptiness, without knowing whence it comes. At this point, love is perhaps not faroff, but it is difficult. You have to go back to the time before the pit, and know when and how it began to open up. At my age that is ineluctable. The substitution of fear by lucidity is what I call ‘dignity’. It is then that it turns out that love was neither far-off nor difficult.

The word ‘dignity’ comes from the Latin dignus, ‘worthy’, and this meaning evolves into the more complex ones of ‘worthy of respect’ and, more importantly, that of ‘self-respect’, which is the meaning that interests me. This dignity which is respect for oneself leads towards love, which penetrates at the same time through intelligence, feeling and sensuality, which occurs inside each one of us and which is only circumstantially to do with public activities dedicated to the most needy, actions which belong, whether implicitly or explicitly, to the realm of politics.

Loving is complex enough to need all the tools and skills we acquired during our apprenticeship. I have found no better way of loving others than through the practice of poetry, sometimes as reader and other times as poet – I have stated more than once that for me the two options are one and the same – and putting, whether composing or interpreting a poem, the same honesty that I would desire and attempt to practise in any aspect of public or private life. I think that this exposition is possible because poetry has the intensity of truth.

Whatever a poet is, that will his poems be also: and there is no one harder to deceive than good readers of poetry. In the long run, a person of culture is someone who can tell Xuang Tsé from a guru of famous singers, a work by Montaigne from a self-help book. There is not a single good poem in which its author has not implicated himself or herself in some way right the way through. It is this that makes of it an act of love. ‘somebody loves us all’, as the wonderful final line of ‘Filling Station’, by Elizabeth Bishop, says.

In the midst of all this, the kind of poetry that most continues to interest me moves in a territory that I would call prudent, avoiding, in its relationship with the mysterious, the two extremes towards which the fallacy of originality is always attempting to push it. On one hand, there is the devaluation of the mysterious, which has already converted one part of the contemporary plastic arts and music into something that is alien to risk and emotion, and therefore to truth. The other extreme consists in emphasising it in an exaggerated way, that is to say, in ignoring the fact that even the mysterious, or especially the mysterious, ought to be treated sensibly. That the meaning or explanation of something may be unknown does not imply that any explanation whatsoever may be acceptable, however outlandish it may be. In spite of its exactness and concision, poetry can never be a short cut.

My own time has fled and left me alone in another time but my solitude is a luxurious one. It makes me think of Machiavelli’s final exile in the rural world of his childhood, of those inns where, as he relates in his memoirs, he talked only to rough, uncultured peasants. But when night came he set a great table with the best and finest cloths, vessels and glasses, which he had brought from Florence, and he supped and talked with the wise men of Antiquity. As for me, in this other exile which is, by its very nature, the final stage – long or short – of life, I feel that I myself am my own interlocutor. I do not now have time to improvise, I should have already spoken, long since, with the wise men of ancient times or of now, so that, through my poems, I might find myself with myself in the territory of dignity. The dignity of not being afraid of my fate.

But there comes a day when the past demands order and, thus, special attention for the mysterious question of memories. Because past and future disappear at the same time, as if by some law of physics, and more and more I have the feeling that the mind has not kept random fragments but rather the essence of the past. That is, what we remember, albeit not true, is, however, the truth. And truth – and I think this is what Josep Pla means when he speaks of poetry and biographies – is the deep aim of poetry. Therefore, the poetry that one has read, just like the music that one has listened to, are some of the elements, and probably not the least important ones, that intervene in the making of this essence.

Because poetry is a tool to manage pain and happiness, especially in their most domestic aspects, sadness and joy, the management of which depends on what is saved from the past. This essence is the subject of the poems in this book. As I was writing them, verses would emerge around a memory, which would fight with strength to get hold of the poem. Then I had to return it harshly to the exact role that it had to play, because what the memory wants to explain when it appears is still very far from the truth.

I feel that I come from a time marked above all by the fear at the end of the civil war, by the silence of executions and of prisons with which the victors exerted their vengeance. With the elders in the house taking care that I wouldn’t be cold or hungry. That is where my Houses of Mercy come from. The ultimate meaning of every poem. But I realise that in order to understand a memory I must be able to connect beginnings and endings, that in order to understand what my grandmother represented for the beginning of my life I had to be able to compare it with what the life of my daughter Joana, as well as her death, represented much later in my life. I need to connect the time during which I wrote my last books of poems with the time that I spent alone with my mother in that village where she was a teacher.

And I also have to link my current idea of what poetry is with the teacher who taught me to write without grammar, directly. It took me years to distinguish a preposition from an adverb, but from the first moment he taught me to write correctly. The poet that I am has lived off this. Of course he taught us all this in Spanish, because I never heard Catalan at school. This repression carried out by means of the amputation of speech is one of the most durable and cruelest ones. I know now that I will die with this fear and this fragility surrounding the perception of my tongue, which means, also, of my life.

Something cries out in our first memories. Their austere clarity, like a bird’s first flight. They are the only primal thing that we have left. A fierce joy despite having been born amid the horror of a murderer’s country. The child knew what the old man can confirm now: that we must know how to use loneliness as a way of dealing with pain and misfortune, and with the cruelty with which this country has always imposed oblivion. All this is now part of my order, my common sense.

I know it is not cautious to search the places of memory if I don’t want to endanger the meaning, feeble and distant, that those days still have. I must never look for the places of memory in real sites. There is a relationship with one’s own falsehoods that could never bear any type of existence beyond the mind. I look at the sky, I see the clouds moving like noiseless trains. The sky is the only thing of which I can say that it is – despite Heraclitus – the same as in childhood. Illusion is the sky’s strength. I mistrust memories, just as I mistrust sex, but both tie me to life. We always mistrust the most important things, it’s our cowardice.

Beyond the mezzo del cammin, life also gets us used to the presence of distances, whether we look backwards or forwards. This becomes more and more evident as we grow older, of course, until one day we realise that the distances have gradually disappeared and that wherever you look everything is equally close. It is not an uncomfortable feeling at all, because it means that after a life of playing against so many forces one begins to have one of the most powerful forces on one’s side, namely indifference.

But indifference in the sense of a lack of feeling in favour or against, and thus applicable to a person as much as to a star. Not indifference in the sense of an absence of interest, which is close to the meaning of the word selfishness. The indifference I refer to avoids the anxiety about that which is not fundamental and for that which is inevitable, that which, being important and even transcendental, we will never be able to change. A neighbour of lucidity, it liberates us precisely from what is superfluous and from what is useless.

So far, poetry has been my life, and it continues to be so. Nothing has had power over me if I have been allowed to write. The circumstances that without poetry would have weakened me have made me stronger. The language I speak and the language in which I write poems are the same. So did the poets from whom I learned this, like Gabriel Ferrater or Philip Larkin. Others, on the contrary, have stressed the difference between spoken language and the language of the poem, as in the case of Josep Carner. But all of them have taught me that inspiration cannot come from anywhere but one’s own life, however distant or odd the poem may seem.

The reading of a poem, which is a very similar operation to that of its writing, is also done through the life of its reader. This is why I think that before doing an erudite reading one should really read the poem: leaving on one side significations, interpretations or critical analyses, letting nothing interfere, let alone observations made from places very far from the simple and profound penetration of words in our mind.

To put it differently: it’s necessary to be left alone with the poem. This loneliness may be uncomfortable sometimes, and we may then shut ourselves off with the verses, surrounded by a library – real or made of accumulated readings – of literary and philological studies. Then, obviously, there are diverse, perhaps many, possible interpretations, all different from each other, and one would not know with which one to agree. We may leave the real reading for another occasion, or it may happen that we decide to adhere to one interpretation and to consider the poem to be read thus. It’s the same thing that can happen to someone who looks at the paintings of a museum while they listen to the flood of information coming from an audio guide: that they finish the visit without having really seen the works.

If a poem moves a reader, it does so through their life. And it does so, not through that which is accessory in the moment of reading, but through that which is fundamental. As if each life were a well from which to descend to one single stream. The poet descends from his well: the only characteristic is that a good poem reaches this deep stream while a bad poem does not go deep enough, it remains too high, dry.

Even if they are not very learned, if a person feels with emotion that what they have read expresses some aspect of their conscience or of their life, then this person has understood the poem. It is for this reason that a poet will always be wise to listen to and to consider an observation about a poem, whoever it may be coming from, as long as it originates from this kind of reading. Because anyone who reads a poem in this manner is using their most noble faculties on the highest level. Incidentally, in this book I have to thank Mariona Ribalta, Pilar Senpau, Ramón Andrés, Luis García Montero, Josep Maria Rodríguez, Mercè Ubach and Jordi Gracia for readings of this kind. And, especially, in this English edition, I have to thank the poet, Anna Crowe, my friend and translator. If the best of me is in my poems, she has always managed to convey this to English readers.

Poetry is the form of expression that least resorts to artfulness, ornament, the one that is farthest from persuasion or from the trickery of pretending to offer what it does not offer. A poem does not manifest itself anywhere but in relation to the life of whoever is reading it, and the poet will have only been its first reader. Knowledge and culture act in the long term, they impregnate and change the person, leaving them in a state of reception more powerful and refined. But good teachers know that if someone approaches a poem with the help not of their own life (and therefore of their formation) but only with the help of information, then this person has not yet begun reading the poem.

We must stay alone with the poem, that is, stay alone with our own fear and ignorance. To accept that we cannot concretise the order that we are gaining in our interior in anything material. That we cannot say why our strength increases as we read it. All this can cause anxiety and even fright and, sometimes, it makes erudition be understood as a reassuring security net. It reassures but at the same time it prevents us from running the risk of poetry and of feeling its vertigo when a poem speaks to us directly. This is why poetry is one of the most serious resources to deal with morality’s bad weather. Its appearance must have been a crucial milestone in the history of humanity. As crucial, for example, as the appearance of the house, of architecture, that liberation of the human being from the cave, a first sign of individuality.

Because that which is impersonal, that is to say objective, cannot help to mitigate the effects of moral suffering with dignity, which is basically caused by loss and absence. No consolation can be of use if it doesn’t speak directly to a you. This is why, tired of ideologies and abstractions, to suddenly encounter a force that works, without any kind of intermediary, on our subjectivity, that accesses the centre of sadness, which is what poetry does, can be so important. If our interests are only occupied by issues like politics, it means that we are putting the accent on what is gregarious in us. And everything that is gregarious tends to nourish contempt. Profound admiration, the type that is not mimetic, comes from individuality. That is, from the you to whom the poem is addressed.

JOAN MARGARIT

Sant Just Desvern,

September 2010–September 2014

Reprinted from Love is a Place (Bloodaxe Books, 2016)

Leçons de vertige

Anthologie établie par Noé Pérez Núñez. Ed.”Les Hauts-Fonds” 2016

FOREWORD – Sharon Olds

I love these poems for many reasons. When I first read Joan Margarit, I heard a powerfully distinctive voice, a spirit of great freedom and energy, humaneness, mischief, and depth.

In these naked, subtle, clear poems, surprise and wisdom are often right next to each other. There is often a doubleness going on in a poem – lots of pairs of ions, the magnetic positives and negatives which hold matter together. This gives his poems a sense of naturally occurring disorder and order, and a welcome absence of wilful craft. There is an exhilarating sense of the spontaneous, the organic – of happenstance and chance. And at the end of a good number of his poems I have the desire to scream – as at a theorem proved, or a victory.

Joan Margarit’s work is fierce, and it is partisan – it is on the side of fresh perception. He’s a fierce protector of his precise truth, like the bees – like a big bee – with honey. His abstractions and his daily objects are given to the reader with equal, deft, homemade tenderness and brio.

Often, at the beginning, a Joan Margarit poem will locate us. ‘It was a top-floor flat.’ Many poems start up quietly, from within an ordinary situation. And then, suddenly, we’re in deep, off-beat thought and feeling. And a Joan Margarit poem often has a turn at the end, as well as a reversal – sometimes a double reversal. Reading him, we are in the world of history, wit, imagination, dream, and memory. At the same time, it is the plain real intransigent world.

What is so unusual in Margarit’s work? I think it is the juxtaposition of the everyday syntax with his intimacy and wisdom – the combination of clarity and accurate subtlety which honours the basic mysteriousness (unknowability) of life.

I love Margarit’s frankness – sexuality a part of life like food, sleep, death, health, illness – and his unflinchingness. He’s stoical – and singing. And defenceless – but for basic human integrity and dignity.

13

Margarit Love Is a Place 1-192_10.5/14 Ehrhardt D8vo 19/06/2016 22:53 Page 13

Joan Margarit has what I’ve heard some great quarterbacks have – equal ability to turn in any direction at any moment. I think samurai have that. I think in U.S. football it’s called ‘broken field’.

There is a lot of change of direction within these poems – and many moments of Satori! The experience of reading him feels the way consciousness itself feels.

Each of Margarit’s poems is its own being, like a living creature with its own body-shape and voice, its own breath and heart-beat. His poems live and breathe in their natural habitat. They are elegant and shapely. And sometimes they seem almost overheard, as if they are singing in the voice the mind uses when talking with itself or with its close close other. It is common enough speech, and it is brilliant, too, sensually beautiful (but not too beautiful) and with a genuine, just-conceived feeling. Those of you who know Joan Margarit’s work, welcome to its most recent incarnation!

Those who are coming to it for the first time – it’s good to have your company. Here is our brother, his genius quietly electric on the page.

Sharon Olds

La poesia no és un ofici, és un miracle

Article de El País

Patricia Gabancho

25 de maig de 2016

Uns senyors amb guants blancs que tractaven els papers admirablement. És la imatge que reté Joan Margarit (Sanaüja, 1938) del trasllat del seu fons documental a la Biblioteca Nacional de Madrid. “Però no hi ha tema”, adverteix. “Va ser una casualitat. Vaig rebre en pocs dies dues cartes, l’una de la Boston University i l’altra de la Biblioteca Nacional. Deien que els interessava que fes donació del llegat, sense oferir res. Bé, la Biblioteca Nacional em va dir que hi hauria una desgravació fiscal, que al final va resultar ser mínima”.

—No va contactar amb les institucions catalanes?

—No…! No sóc tan important. La veritat és que m’ho vaig pensar. Em feia gràcia Boston, però al capdavall vaig entendre que era una putada per al dia que volgués veure una foto o buscar un paper. Va guanyar la proximitat.

“Vaig cedir el meu llegat a Madrid simplement perquè m’ho van demanar”

I així va marxar cap a Madrid, a final del 2011, tot el llegat de l’autor, inclosa la documentació sobre arquitectura i les cartes. “Tenia això abarrotat de papers. Quan van venir a buscar-ho vaig tenir una alegria. No sóc un sentimental”, diu. Per demostrar-ho, afirma que a la biblioteca no té cap llibre que no hagi llegit o que no sigui d’un amic. “Sí que hi són els que penso llegir. Fixa’t, allà dalt: hi ha els vuit volums de la Decadencia y caída del Imperio Romano, d’Edward Gibbon. Fa vint anys em vaig dir: ‘Això és el que llegiràs quan siguis vell’. I encara no”, diu.

—A Catalunya tenim una administració distreta.

—Distreta, sí. M’agrada la paraula. No és ofensiva.

Però jo sí que volia que fos ofensiva…

Margarit acaba de publicar L’ombra de l’altra mar (Nórdica), dedicada al record del seu amic Josep Maria Subirachs, amb quadres de l’escultor, i Des d’on tornar a estimar (Proa), un títol molt adequat perquè els poemes sempre comencen amb una referència concreta, un espai físic. “Es tracta d’arribar tan lluny com pugui partint de molt a prop. La poesia comença amb una inspiració, que és la capacitat de relacionar coses que no són relacionables”. Com una metàfora? “Sí. Però això no és res; cal treballar-hi”. Margarit sol recuperar records, alguns molt durs: afusellaments, el pare a la presó, la misèria, la sorda violència sobre els vençuts, però tot això revé sense ombra de ressentiment. “Fins que tenia nou anys tot era anar i venir, vam canviar onze vegades de domicili”, recorda. “Però l’art no es pot basar en el ressentiment, ni en l’odi”.

“Escric des dels 18 anys, cada dia, mai en prosa, o a penes en prosa. La primera vegada que davant un llibre meu dic: “És això”, tinc 40 anys; vol dir que he estat 20 anys llençant llibres sencers. Amb un problema afegit, que és la llengua. Recordo una escena, de nen. Anava a escola amb un amic, li vaig dir alguna cosa i em va caure un clatellot d’algú uniformat, no sé qui. “Habla en cristiano”… Amb els anys, la meva reflexió va ser: la poesia és cultura, la cultura es fa en castellà, escric en castellà. Aquesta equació serveix per a tot, excepte per a la poesia. Si la cultura és una catedral, la poesia n’és la cripta, que és un forat. Això és la llengua materna… Trigo anys a adonar-me’n. I qui primer me’n va suggerir el canvi va ser Miquel Martí i Pol.

LLETRA A LA NOVA CANÇÓ

Joan Margarit va ser fa poc a Madrid. Recitava amb veu de tro, una veu antiga, des d’un escenari on regnava Paco Ibáñez, que hi tornava a actuar després de dècades de sequera provocada pels governs del Partit Popular. El cantautor va reunir les quatre llengües nacionals en els seus poetes: hi eren també Bernardo Atxaga, irònic; García Teijerio, nostàlgic, i Luis García Montero, jugant a casa. Margarit era una altra cosa. Poemes amargs exclamats en un ritual de comunió. No para de fer recitals, de provocar emocions indelebles com cicatrius.

“Amb el Paco ens vam conèixer en un sopar on hi eren el també editor i poeta Joaquim Horta, José Agustín Goytisolo i gent de París”, explica. Tard, van tancar el restaurant i el Paco va començar a cantar. “Va dir que faria una cançó que no canta mai perquè el fa plorar. I quan comença jo em dic: ‘Caram, això em sona, i després: però si això ho he escrit jo!’.; era Els que vénen, que cantava l’Enric Barbat”.

No sabia, li dic, que havia fet lletres per a la Nova Cançó. “No gaires, una o dues. Li vaig dir al Paco que la cantés ara a Madrid, però no vol perquè diu que té un accent dolent en català”. Somriu: “Li dic que l’accent català ja no és com era. I no em preocupa, perquè sabem el que va passar amb el llatí, que d’allò que ells devien considerar putrefacte va sortir tot, també el català…”, conclou.

—Com és que freqüentava el món literari si no publicava?

—Sí que havia publicat. Camilo José Cela va dir que jo era un “Surrealista metafísic”… Vaig canviar al català i l’any 1980 guanyo un premi amb un llibre que es diu L’ombra de l’altra mar.

—No sembla un títol seu…

—Focs d’artifici. Vaig haver de llençar a la bassa deu llibres més, algun de premiat. No hi són, a les obres completes. D’un castellà sobri però fals, passo a un català carnerià i després torno a la sobrietat per trobar la meva veu.

S’han fet grans els arbres del jardí: li comento que la mirada sempre va cap enrere —“seria idiota si no ho fes: anar envellint, què més?”—, que espai i temps semblen ser les dimensions de la seva poesia, i que potser per això els trens hi tenen tanta presència. Pensa un moment. “Segurament. També és pura memòria. A Rubí vivíem prop de l’estació”.

De jove, Margarit va cometre el gran error de deixar Arquitectura un cop superat el dificilíssim ingrés, previst perquè la professió fos elitista. Decidit a ser poeta, volia una feina que hi tingués relació. Va ser a l’editorial Plaza, tot fent un diccionari tecnològic a partir de diccionaris estrangers. “Llavors m’adono que l’estic pifiant i torno a Arquitectura. I descobreixo la veritat: la poesia és exactitud, puresa, una cosa escarida. Això és el càlcul, que té una lògica, com la té la poesia. M’hi llenço com un animal i als 29 anys sóc catedràtic de càlcul d’estructures. Ja tinc la vida organitzada. I no em costa gens passar de la feina a la poesia, puc prendre notes en un bar. La poesia no se sent vexada, se m’obre estupendament, perquè no li sóc infidel, i això que la poesia és molt senyora”.

Molt senyora: tracta Barcelona de puta. Desolada ciutat que fas de puta, li recito. “Barcelona té la grandesa de posar el cementiri en una muntanya cèntrica, que podia haver estat residència de rics. Hi tinc dues noies; per tant, és la meva ciutat, no hi ha dubte que l’estimo, amb lleialtat. Però se l’han venuda i no hem rebut res a canvi. No sé qui són els amos actuals de la ciutat. Està plena de botigues que venen coses innecessàries: això és molt semblant a la prostitució”. Hi afegeix una altra imatge brutal: la cara maquillada de la mare morta.

—Sí. El passeig de Gràcia. Maquillada pel tio de la funerària, la mare. Però és la meva mare, la meva ciutat.

—Una ciutat que tenia una burgesia culta i una classe obrera que sabia poemes de memòria, diu el mateix poema.

—És la meva àvia. La van enviar de minyona a Barcelona amb 12 anys, des de Sanaüja; va anar a casa d’un banquer del carrer Ample. L’àvia llegia cada dia el diari tot resseguint la línia amb el dit, a poc a poc. Sabia poemes de Verdaguer: va plorar quan va morir. Tot això es va perdre el 1939, però s’hauria perdut igual.

Parla dels oficis, de quan calia un fuster per tenir una cadira i que aquest fuster era més bo al cap de deu anys, i el metge també. “Això és la dignitat i la seguretat de l’ofici, i això ja no existeix. Avui parlem de curro. En poesia, però, ningú et garanteix que esdevinguis millor amb els anys”.

“La poesia és remenar la ronya que tenim dins, recuperar les coses més subtils i amb paraules, i no amb res més, expressar-ho i enviar-ho a algú que no conec i que aquest algú ho llegeixi i digui: sóc jo. Això no és un ofici, això és un miracle”.